Before Tae-il died, he asked his mother to do something that he could not accomplish. Lee So-seon (1929–2011), his mother, promised to fulfil her son’s wish, and this effort continued until her death.

When her son passed away, Lee So-seon refused to have a funeral and went into a protest, demanding eight provisions from employers and government authorities as follows: paid holidays, legal wage increases, 8-hour work hours, regular health check-ups, women’s menstrual leave, abolition of attic sewing sweatshops, and support for unionization.

Lee So-seon did not give up despite all types of threats and negotiations from the government. Conscious of the deteriorating public opinion, the government authorities accepted the proposal, and finally, on November 27, 1970, the Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union (Cheonggye Apparel Markets’ Labor Union) was formed.

The Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union was the first outcome of her struggle. Lee So-seon became known as the “mother of laborers” while working as an advisor to the union.

After “The October Restoration” in 1972, the government’s suppression of labor unions intensified. Nonetheless, when the union achieved certain results, such as reduced working hours, raised wages, and operation of labor schools, the government authorities attempted to physically dissolve the union. Activists, who had been supporting the union, were put on trial for violating the Emergency Measures, and Lee So-seon, who protested, was detained for contempt of court.

In 1977, after Lee So-seon’s release, the Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union began a fierce fight demanding the guarantee of three labor rights (namely, the right to collectively organize, the right to collectively bargain, and the right to collectively act, as stipulated in the Republic’s Constitution). Lee So-seon served another year in prison, and immediately after her release in 1978, she participated in a demonstration by workers of Dongil Textile but was severely beaten and suffered a permanent disability.

In early 1981, the new Chun Doo-hwan military government ordered the dissolution of the Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union, which was facing a crisis. Cheonggye Clothing’s workers and Lee So-seon fought fiercely for the legalization of the union, and in 1988, the union was finally legalized after the 1987 Great Workers’ Struggle.

Lee So-seon expanded her activities to include the democratization movement. In 1986, she founded the National Association of Bereaved Families of the Democratization Movement and served as its first president. In 1989, they held a sin-in for 135 days, demanding an investigation into suspicious deaths. From 1998 to 1999, she also contributed to the enactment of the “Act on the Honor Restoration of and Compensation to Persons Related to Democratization Movements” by holding a long-term sit-in protest in front of the National Assembly for 422 days.

During her struggles while supporting the workers for 41 years, Lee So-seon was arrested over 250 times, detained 180 times, and imprisoned for 3 years.

When her son passed away, Lee So-seon refused to have a funeral and went into a protest, demanding eight provisions from employers and government authorities as follows: paid holidays, legal wage increases, 8-hour work hours, regular health check-ups, women’s menstrual leave, abolition of attic sewing sweatshops, and support for unionization.

Lee So-seon did not give up despite all types of threats and negotiations from the government. Conscious of the deteriorating public opinion, the government authorities accepted the proposal, and finally, on November 27, 1970, the Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union (Cheonggye Apparel Markets’ Labor Union) was formed.

The Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union was the first outcome of her struggle. Lee So-seon became known as the “mother of laborers” while working as an advisor to the union.

After “The October Restoration” in 1972, the government’s suppression of labor unions intensified. Nonetheless, when the union achieved certain results, such as reduced working hours, raised wages, and operation of labor schools, the government authorities attempted to physically dissolve the union. Activists, who had been supporting the union, were put on trial for violating the Emergency Measures, and Lee So-seon, who protested, was detained for contempt of court.

In 1977, after Lee So-seon’s release, the Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union began a fierce fight demanding the guarantee of three labor rights (namely, the right to collectively organize, the right to collectively bargain, and the right to collectively act, as stipulated in the Republic’s Constitution). Lee So-seon served another year in prison, and immediately after her release in 1978, she participated in a demonstration by workers of Dongil Textile but was severely beaten and suffered a permanent disability.

In early 1981, the new Chun Doo-hwan military government ordered the dissolution of the Cheonggye Pibok Labor Union, which was facing a crisis. Cheonggye Clothing’s workers and Lee So-seon fought fiercely for the legalization of the union, and in 1988, the union was finally legalized after the 1987 Great Workers’ Struggle.

Lee So-seon expanded her activities to include the democratization movement. In 1986, she founded the National Association of Bereaved Families of the Democratization Movement and served as its first president. In 1989, they held a sin-in for 135 days, demanding an investigation into suspicious deaths. From 1998 to 1999, she also contributed to the enactment of the “Act on the Honor Restoration of and Compensation to Persons Related to Democratization Movements” by holding a long-term sit-in protest in front of the National Assembly for 422 days.

During her struggles while supporting the workers for 41 years, Lee So-seon was arrested over 250 times, detained 180 times, and imprisoned for 3 years.

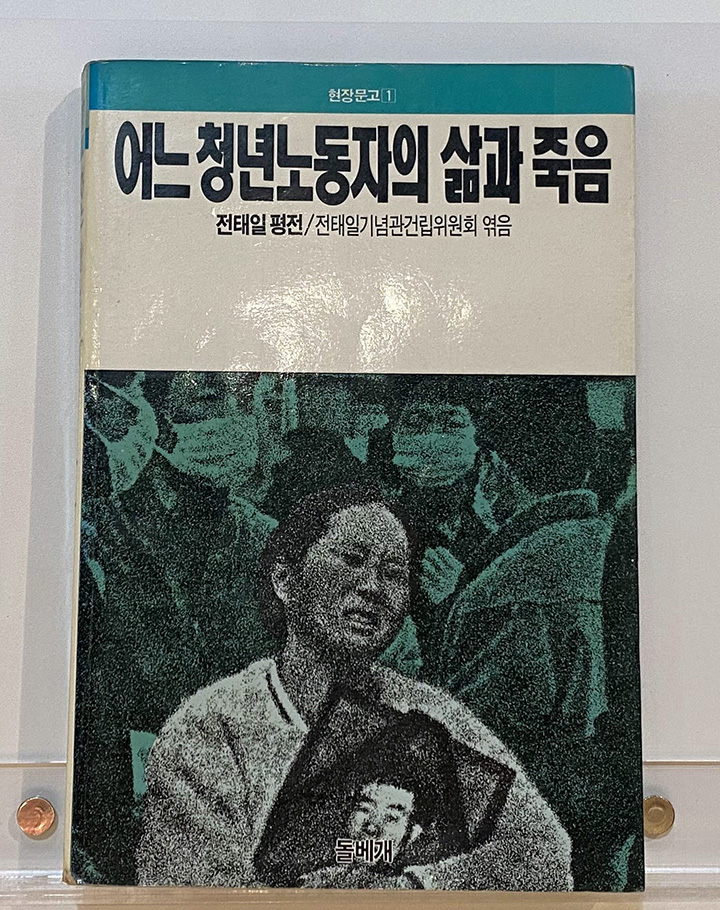

Cho Young-rae

Cho Yeong-rae (1947–1990) made Tae-il’s life and spirit known to many people by writing A Single Spark: The Biography of Chun Tae-il. While serving in prison and being wanted for the student movement and the 1974 National Democracy Youth Student Confederation incident, he encountered Chun Tae-il’s memoirs and wrote them based on the testimonies of Lee So-seon and Tae-il’s friends. However, it was difficult to publish it under the Yushin regime of Park Jung-hee’s government; therefore, it was first published in Japan in 1978. In South Korea, it was published anonymously in 1983. It was published under the name of Cho Young-rae in 1991, one year after his death. Subsequently, it was translated into various languages and influenced labor movements in many countries.

The History of the Labor Movement

Tae-il’s protest in 1970 led to a rapid spread of social interest and awareness on the seriousness of labor conditions and resulted in intellectuals and workers boldly joining solidarity struggles.

After Chun Tae-il’s self-immolation protest, democratic labor unions were formed in factories. Numerous labor unions supported and joined each other to develop a democratic union movement.

The Park Chung-hee regime tried to block the three labor rights, but the YH Trade branch of the National Textile Workers’ Union and other branch-level unions worked hard to improve working conditions and defend the democratic branch-level unions. In 1979, the new military government of Chun Doo-hwan carried out a total revision of the labor law in the name of “social purification movement,” “trade union clean-up measures,” and “three bans” (prohibition of multiple unions, prohibition of third-party intervention, and prohibition of political activities).

However, the labor movement entered a new phase as university students, workers, and farmers risked their lives to resist the military regime and demand social change. Numerous university students entered the labor field. After the declaration of surrender by the Chun Doo-hwan regime on June 29, 1987, the Great Workers’ Struggle escalated, bringing about a change in the landscape wherein all wage earners became aware of and joined the labor movement.

After Chun Tae-il’s self-immolation protest, democratic labor unions were formed in factories. Numerous labor unions supported and joined each other to develop a democratic union movement.

The Park Chung-hee regime tried to block the three labor rights, but the YH Trade branch of the National Textile Workers’ Union and other branch-level unions worked hard to improve working conditions and defend the democratic branch-level unions. In 1979, the new military government of Chun Doo-hwan carried out a total revision of the labor law in the name of “social purification movement,” “trade union clean-up measures,” and “three bans” (prohibition of multiple unions, prohibition of third-party intervention, and prohibition of political activities).

However, the labor movement entered a new phase as university students, workers, and farmers risked their lives to resist the military regime and demand social change. Numerous university students entered the labor field. After the declaration of surrender by the Chun Doo-hwan regime on June 29, 1987, the Great Workers’ Struggle escalated, bringing about a change in the landscape wherein all wage earners became aware of and joined the labor movement.

Relevant exhibits

The Life and Death of a Young Worker, Chun Tae-il Memorial Establishment Committee, 1983

This was the first biography of Chun Tae-il published in South Korea in 1983. Due to the oppression of the military dictatorship, the name of the author could not be properly revealed; therefore, it was published as a compilation by the Chun Tae-il Memorial Establishment Committee, and much of the manuscript was revised. Subsequently, only in the revised edition in 1991, when the military dictatorship ended, was it revealed that the author was Cho Young-rae, and the original work was then simultaneously published.

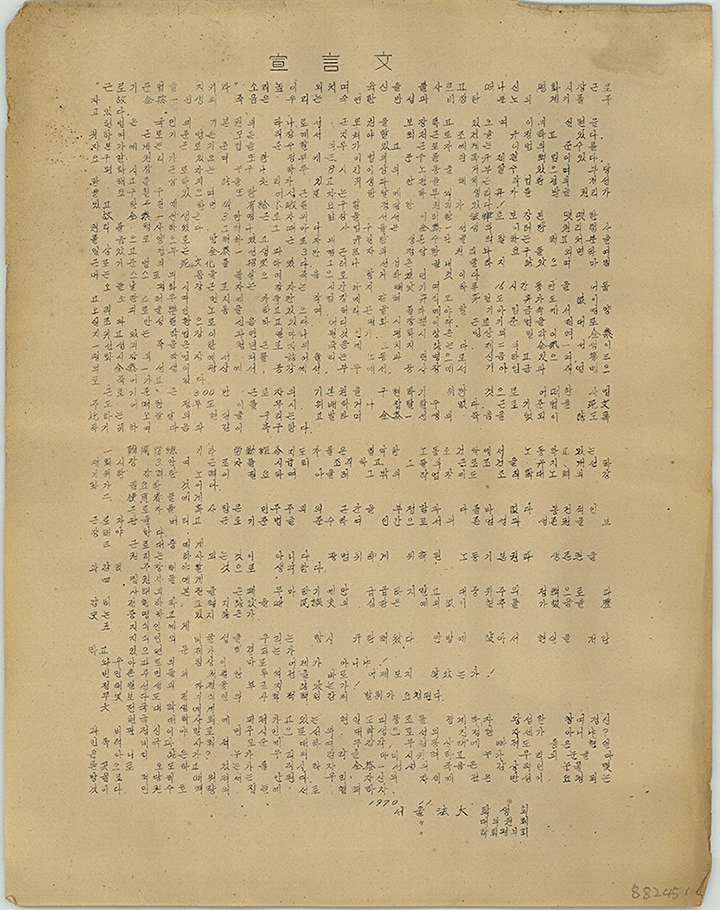

Joint Declaration of Seoul National University’s Law School Student Association, Law School Representatives Association, and Law School Study Circles Council, November 1970

This declaration was jointly announced by three student councils of the Seoul National University Law School to condemn the deaths of Chun Tae-il and countless workers at work sites who did not abide by the Labor Standards Act. Accordingly, its content insisted that employers comply with the Labor Standards Act and that university students nationwide reflect on Tae-il’s death and work together to improve their working environment.

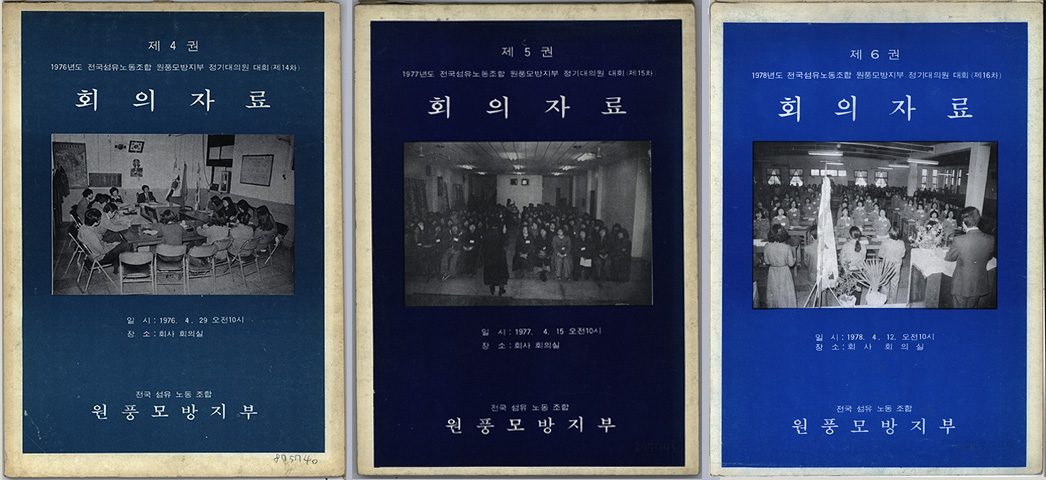

Wonpung Woolen Clothing Branch of the National Textile Workers’ Union Delegates Meeting Materials, 1976–1978

These are Volumes 4 to 6 (14th to 16th) of the meeting materials for the Wongpung Woolen Clothing branch delegates meeting of the National Textile Workers’ Union. At the time, major activities and resolutions, list of delegates, table of organizations, history, and various activities were commonly included in the meeting materials.

Report of the Dongil Textile Incident, 1976–1978

This document reveals the truth of the incident that occurred on February 21, 1978, when workers who were instigated by employers threw dung at female workers to interfere with the election of the Dongil Textile branch delegates of the National Textile Workers’ UnionAfter the incident, employers dismissed the union members, and the National Textile Workers’ Union declared the Dongil Textile branch as troublesome and expelled the branch executives.

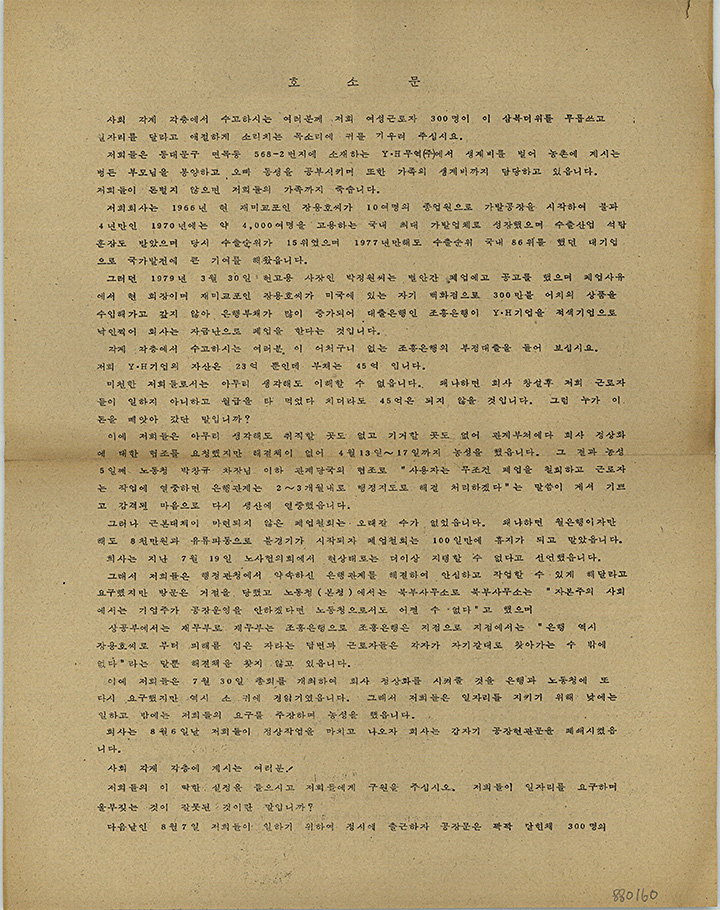

Letter of Appeal by the YH Trade Branch of the National Textile Workers’ Union, 1979

This letter appealed to support 320 YH Trade female workers who were protesting the unilateral closing measures of the factory.